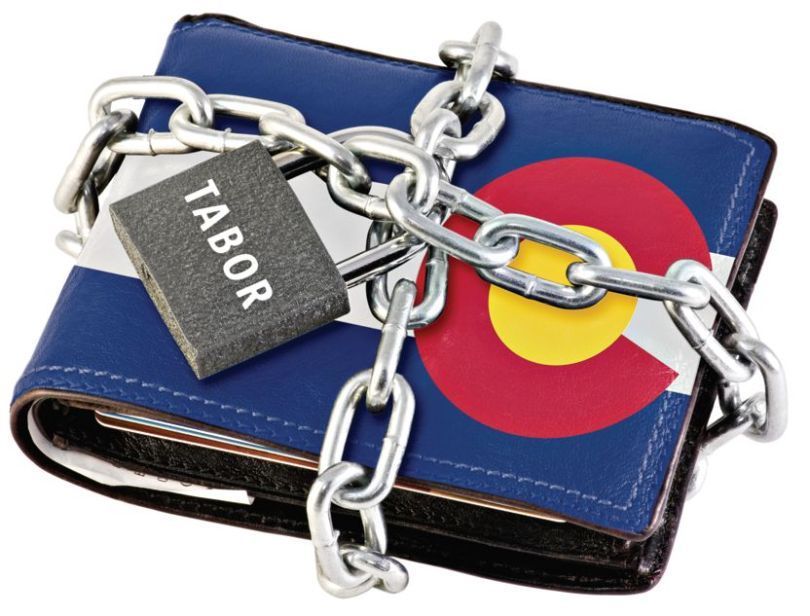

TABOR: What It Is and Why We Don’t Need It

February 23, 2018

TABOR is Colorado’s Taxpayers Bill of Rights passed in 1992.

In summary, TABOR exists to protect taxpayers from the government. It strictly limits how much revenue the state can keep, and how much it must spend. Whenever a change in taxes is proposed, the people vote on it, and the end result is that the people get to choose whether or not taxes are raised or lowered. Sounds pretty good, right? Wrong.

The first problem with TABOR is that it gives the power of choice to the people. Now, don’t get me wrong, I do believe that government by the people is crucial to a democracy; I’m not a socialist. However, I also believe in government for the people. I think that the vast majority of citizens do not have a clear concept of what would be best for themselves in general. Maybe they do on an individual level, but your average American will not have any idea of what is best for the country, or even the state, as a whole. The government, with all its faults, is in place for a reason: they should know more about their citizens as an entity (although not individually) than the citizens do.

One example: when the people are well off, it would make sense to raise the taxes (slightly, nothing extraordinary) to have money for when the people are worse off. With TABOR in place, the people get to decide that. Do we want to pay more taxes, or do we want to pay less taxes? Hm, let me think about that one. I’m not saying that we as citizens shouldn’t have a say in what the government does–we certainly should. As citizens, we need to tell them when they step out of line, and limit them accordingly. But taking away practically all the power from the government is limiting them too much–as it is now, the state government has very little power when it comes to taxes.

The other fundamental problem with TABOR is that it cuts considerably into public school funding. TABOR supporters deny this, saying that, firstly, TABOR contributes to school funding, and secondly, that schools don’t really need more funding, they simply need to spend their money more wisely. For more on the controversial funding vs. spending issue with schools, read February 12th’s Haystack article The Fund-amental Problem With Education and Money.

So, does TABOR contribute to school funding? To determine the answer, we need to look back several decades. In 1992, TABOR was passed, and from that time, schools have not even been receiving enough money to keep up with inflation. Even mill and bond levies must go through the people, and as a result, the schools have lost not only significant government funding, but have found that TABOR even limits their ability to raise money on their own.

In the year 2000, concerned citizens voted for Amendment 23, an amendment to the state constitution which basically attempted to get more state funding to the education system. In summary, Amendment 23 established a minimum amount of money, the “base,” that had to be increased by inflation plus one percent for the next ten years, and by inflation afterwards. An amount was then added onto this “base,” determined by a combination of factors including district size, number of “at risk” (free and reduced lunch eligible) kids, and local costs of living, to name a few. The amendment also required the total funding for all categorical programs (programs established by the state to support the basic core programs, such as English language proficiency programs and special education) to increase by the same amount.

Another area in which Amendment 23 attempted to get more funding to the schools is by creating the State Education Fund, which was funded through a tax of one-third of one percent of federal tax revenue. This fund was completely exempt from TABOR limitations. If legislators did want to take from it, Amendment 23 required them to increase the General education fund by more than 5% annually.

This amendment was a great idea, in my opinion, but it didn’t work out the way the voters planned. When the recession hit, state taxes decreased by nearly 13%, so in 2009, state lawmakers decided to reinterpret Amendment 23. They decided that, due to extenuating circumstances, the “base” minimum amount required for the educational system prescribed in the amendment was actually a maximum amount–and they cut all of the money going to the additional factors, leaving the schools worse off than they were before.

So now, the schools were only getting their “base” amount, without the additional funds for their additional factors. The places hit hardest were the ones boasting the most of these factors: “rural schools, those serving high populations of at-risk students, and those serving communities with a high cost of living,” according to the Ft. Collins Coloradoan. This reduction of funding, based on these factors, is called the Negative Factor by opponents of TABOR, although TABOR and its advocates prefer the term “Budget Stabilization Factor.”

As a result of TABOR, the Negative Factor (I’m sorry, I mean the Budget Stabilization Factor), and the Gallagher Act from 1982 (which, in summary, decreased the percent of property value that is subject to taxation, which was a large part of school funding at the time), school funding has decreased drastically over the past 50 or so years.

In about 1988, according to a graph provided by the National Center for Education Statistics, Colorado’s spending per-student started to decline from the National Average. By the time TABOR was passed in 1992, Colorado’s per-student average was almost $400 less than than the national average. Keep in mind, that’s $400 per-student. It’s also $400 in 1992, which is not the same as $400 today–taking into account inflation, those $400 would be more than $700 in 2018. While the per-student spending average did not decrease continuously (in 1994 it went up slightly, also in 1997), it did continue its slow and steady downwards trend. By 2000, when Amendment 23 was passed, Colorado’s per-student spending average was nearly $700 below the national average. By 2011, Colorado was spending almost $2,000 less per-student than the national average. Imagine a small school of 500 kids here in Colorado. That school has $1 million less than a similar school in another state that is closer to the national average.

Two thousand dollars per student is quite a large amount of money. According to the Colorado Department of Education, there are 910,280 K-12 students in Colorado (2016-17), and Colorado should be spending (roughly) $2,000 more per student. Thanks to the Gallagher Act, TABOR, and especially the Negative Factor, we are not spending that much, and because of this Colorado’s educational system is currently $1,820,560,000 behind the national average–that’s almost $2 billion!

So, with TABOR, we have freedom from government control. However, we are also taking away $1,820,560,000 from our educational system. TABOR has, most likely, contributed to Colorado’s economic prosperity. In fact, they have probably contributed somewhere close to $1,820,560,000. So the question is, is this $1,820,560,000 really helping the state? What do we value more–our schools, or our money?