School Currency: Counterfeit Benefit?

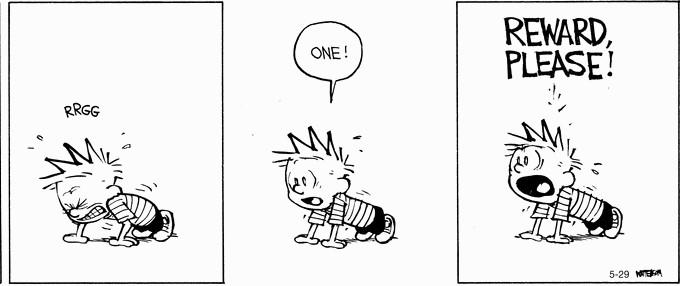

Calvin in Bill Watterson’s classic comic strip magnificently demonstrates the expectation of getting rewarded for doing petty good actions, which the school currency system encourages.

February 20, 2018

Thinking back on my elementary school experience in Wheat Ridge, my recollections are comprised of a jumble of subjects–new faces, beloved teachers, kickball, and spelling tests.

Now, having siblings in preschool and kindergarten has brought back to me a major classroom dynamic that had slipped from my memory: school currency.

School currency, for those few people who didn’t come from a school where this was used, is basically a form of toy money that teachers award to students for participation in class or good behavior. This money can be used to buy cheap toys from the classroom “store.”

And it is something, in my mind, that is not a positive addition to the elementary classroom.

The rationale behind this practice, I will grant, is not evil. As far as I can tell, school currency is just a different way to reward students for being good members of the school community, as well as trying to teach them basic money value, encourage good spending habits, and reinforce goal-making. This system, however, is far from flaw-free; so much so, that I think that it would serve the classroom and students better to discard it.

Probably the biggest problem with school currency is that although it may get kids to participate or behave well, it makes them do these things for the wrong reason. Kids can learn through it to raise their hands more and talk in class less, but likely just as means to the end of getting some toys from the class store. This means that even if their behavior in class improves, this improvement doesn’t translate to life outside the classroom. As is the danger of all extrinsic motivation, they are just as likely to get hooked on the reward as on the wanted behavior.

Getting rewarded for the good things we do shouldn’t be why we do them. Kids need to realize that as adults, contributing to a discussion, engaging with people at work, or following the law will not guarantee them an immediate check; these things should be done simply because one is a good person who wants to keep the cogs of the social clock running smoothly. Rewarding children for being good and participating in class sets them up with the false expectation that any good action they do will give them something in return. Students need to learn that the primary reason for being active and well-behaved members of the student body is to maintain a more engaged, learning-centered environment, and not to get some cheap toys.

Someone in favor of school currency might counter this by arguing that although it perhaps is not a perfect form of motivation, it does give students an idea of what the financial world is like–teaching them money value, financial skills, and goal-setting strategies.

I would say, not necessarily.

Although school currency can definitely be a good way to teach students that a penny is one cent, a nickel five, a dime ten, and so on and so forth, fake money isn’t always the form school currency takes. At Wheat Ridge 5-8 where I attended sixth grade, our school currency came in the form of little slips of paper called “wolf tracks.” Teaching money value is not a given of school currency.

And neither is teaching financial skills. Although the school currency system does allow for the possibility of kids learning money-saving and goal-setting, elementary school students might not value the more expensive items over the cheaper ones enough to save up their money to buy them. The more expensive stuffed animal, book, or calendar may not be any more fun for a second-grader than a cheap noise-maker, slappy-hand, or similar pointless oddity that so much engaged us when we were that age. It is true that there will be students who do want that more expensive toy and have the discipline to save up for it, but just as often, students won’t think that the price is worth the work–and because of this, they will miss the financial lesson, and maybe even end up with the idea that saving up their money won’t ever do them any good.

School currency is simply not a beneficial addition to the elementary environment. Rewarding students every time they participate in class teaches them to expect reward for things they should do simply because they want to add positively to their community. School currency not only gives students an unrealistic taste of life, but it teaches them materialism without growing their knowledge of finances. Systems like this may improve class participation or behavior in the short-term, but they cause more harm than good in the long-term; and for this reason, school currency is something it would be better to do without.

Chelsea • Jan 21, 2024 at 2:18 pm

I participated in this in first or second grade.

I remember it being so fun it sparked an interest in entrepreneurship and business. I feel like there’s a bare minimum children should learn from this type of education, and then there are children that will go above and beyond. It can show where children’s strengths and weaknesses with money stand, and they can be taught stronger methods of necessary.

Different personality types (mbti) will struggle with different things about it and do better in other things.

There is a lot that can be done with this to overcome it’s potential short-comings and it depends on the teacher as well.

I believe it’d be perfect for homeschool, then they aren’t feeling a need to compete and can be happy with what they’ve earned.

I don’t think it should be long-term, but only as long as it takes to teach them how money works and stuff.