COVID-19 and High Schools Around the States

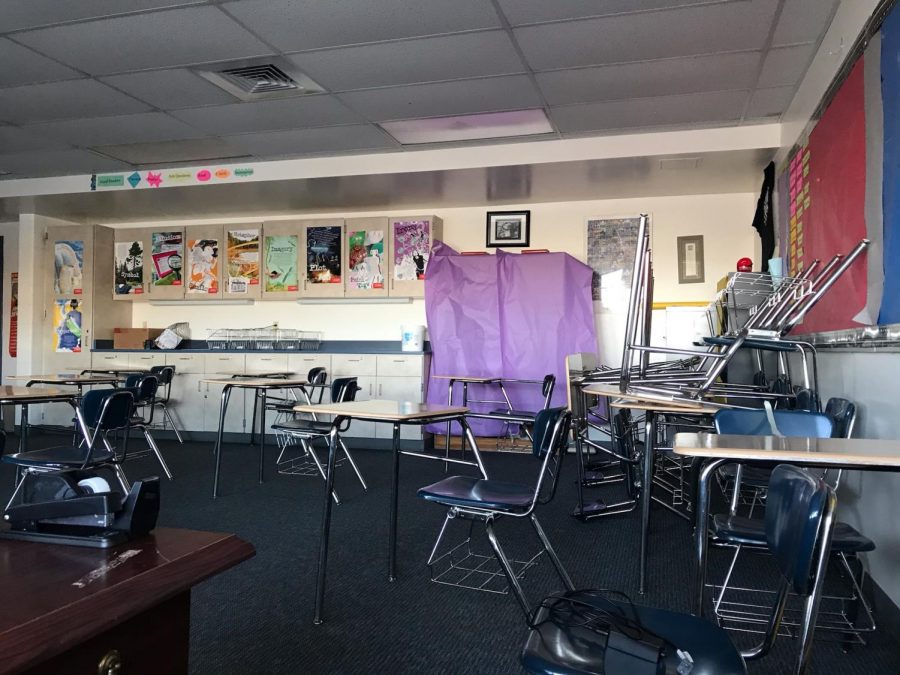

An empty classroom here at WRHS

November 19, 2020

Public school never truly feels normal, not perfectly at least. There’s something about going to the building that just has a weird feeling. So many people have bizarre stories from their time in public high school. But now, more than ever, everything about is different.

COVID-19 has impacted all parts of our society, as we are all well aware, but school has been impacted in ways that we’ve never considered.

Here at Wheat Ridge, our plan for safe learning was a mixture of in-person and online learning. Some people were completely remote, such as me, while others go for two days a week, and do remote the rest of the time. While at school, people are required to maintain social distancing and everyone must wear masks.

Schools everywhere in the United States are handling this differently, however. So I decided to investigate by interviewing a few teachers from different states and schools, so here is how different places are handling the pandemic in schooling.

Over in Missoula, Montana, I interviewed Joe Fischer, who is a high school history teacher at Sentinel High School. The plan for this school is similar to ours. They have hybrid teaching as well, with specific groups of students going on certain days. Tuesday through Friday are all in person days, with the groups switching off every other day. Students do remote work during the days that they aren’t in class. Mondays are fully remote days for students. They also rotate weekly on which periods are actually covered in class.

Pretty much everyone has concerns about how this is working, and Fischer is no different. “I am fearful that we will be on-line 100% of the time … (in the spring) we had a number of students, who did well in-person but really struggled with online work,” he said in relation to concerns.

Fischer also feels that this plan has worked out pretty well, considering classroom size has been cut down to only 50% and the district has been good about getting PPE to teachers and students. And while not being completely in person, Fischer remains close to students simply by being in a smaller class, allowing better connections to be made with students.

The next person I interviewed is an English teacher at Manhattan High School in Kansas and her name is Traci Small. In Kansas, they have similar plans to ours. For example, they provide a completely remote option and a hybrid learning option. There is also a group A and a group B of students, with A students going on Monday and Tuesday and B students going on Thursday and Friday. Wednesday is a remote day for all students so that the building can be sanitized. This plan, according to Small, does well in protecting students and teachers, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have its downfalls.

“Unfortunately, that means that education is suffering … and our sense of community is diminished,” Small said, on the dreary nature of the school schedule.

Much like Fischer’s school, the smaller class sizes at Small’s school allow for better connection with her in-person students. This isn’t the same with remote students, seeing as she has a hard time building that connection with these students.

As a closing regard, Small thinks that schools are doing a good job at keeping students safe, but that they “deserve more.” She also made a point to say that people need to understand how time consuming and exhausting teaching is when done this way.

I also interviewed Lynn Fischer, who is another teacher over in Missoula. She teaches at Hellgate Elementary as a first grade teacher and currently has 19 students, with 15 being in-person and the other four being remote.

The plan for Hellgate is far different than the others discussed previously. They have classes five days a week, without much change besides a mask mandate now in place. Teachers are also required to be with their students 100% of the time, including recess. At the start of the school year, students were also given the option to learn fully remote, and those students, after some trial and error, using a learning program called MobyMax.

In her opinion, Lynn Fischer thinks that as cases continue to rise and hospitals continue to meet capacity, that her school may be forced to transfer to only online learning. To put it simply, she doesn’t necessarily feel safe with the current system and see room for improvement.

“I think we could do better if our class sizes were smaller but what outside of school … is completely out of our control. That is the problem,” Fischer said on the subject.

The last person I interviewed is Michelle Montgomery, who is a Language Arts teacher at John J. Lukancic Middle School, which is located just outside of Chicago.

At the time of the interview, this school is under a hybrid plan like the other schools mentioned, with specific groups going on specific days. Montgomery thinks that as numbers increase, there will be a good chance that her school will transition to only remote learning and teaching.

Montgomery feels that her school has done a good job at keeping her students safe, and she feels that it’s given a unique insight into the home lives of her students. This doesn’t eliminate all concern, however.

“What concerns me the most are the students who are meal deprived and home alone for extensive hours because parents are essential workers,” Montgomery said.

Overall, it seems most schools are working in a hybrid plan, creating a mix of our old way of learning and our new way of learning. Hopefully as we keep going on, we can learn the best ways of learning and adapt to the new challenges. I want to say thank you for all the teachers who took the time to let me interview them. For now, let’s stay safe and healthy to the best of our ability.